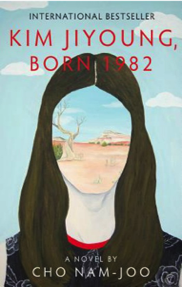

Cho Nam-Joo's debut novel Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 is filled with disturbing illustrations of misogyny in Korea. Like the title itself, each moment is narrated flatly, free of sensationalism and overt emotion, as Cho exposes the chronic dominance of boys over girls, men over women in every facet of Korean society. The book has been translated into nineteen languages (the English translation is by Jamie Chang) and become a rallying cry for women's rights.

Kim Jiyoung, a thirty-three-year-old woman living on the outskirts of Seoul, gives up her job and hopes for a career in marketing to take care of her husband, house, and baby daughter. Shortly thereafter, Jiyoung begins acting strangely. She mimics the voice and mannerisms of other women, predominantly her dead mother and a close friend who recently died in childbirth. At first her husband thinks she is joking around, but Jiyoung doesn't seem to remember impersonating the women from her life. The concerned husband decides to take her to a psychiatrist.

This opening section sets up a behavioral mystery and the anticipation of diagnosing an intriguing malady, or barring that, unearthing a traumatic experience underlying Jiyoung's symptoms. But neither appears to be the case; Jiyoung's life is typical of Korean women. The book is divided into the stages of Jiyoung's life, from childhood and adolescence, through early adulthood, marriage and to her time in therapy, when she is prescribed antidepressants and sleeping pills. The third-person narrative voice remains perfunctory while relaying events with little emotional investment, so the reader is rarely sucked into a scene. Facts, rather than feelings, carry the story. This encyclopedic biography style is reinforced by a dozen or so occurrences of footnoted clinical studies and articles that support Jiyoung's experiences of misogyny.

Reading about the constant undermining of women and girls made my blood boil. School girls cannot play sports because they wear short skirts and dress shoes that prohibit their movement; yet the administration will not permit a change in the very dress code that causes the problem and makes for frozen feet in the winter. Male teachers unnecessarily touch the female students and when the girls report a chronic flasher on campus, no action is taken. Several girls set up a trap for the flasher, but instead of praising them for ridding the campus of the perpetrator, they are given detention and forced to write apology letters for their unladylike behavior.

Jiyoung's mother weighs in on her own experience of dropping out of middle school to work in a sweat shop supporting her three brothers through college. When all were successful, she thought her turn to get an education had finally come. It never did. A “sacrifice made without truly understanding the consequences, or even having the choice to refuse, created regret and resentment that was as deep as it was slow to heal.” By including older generations, Cho shows the universality of women's experiences, and voices this resentment and the need for women to make their own choices.

As Jiyoung enters the work force, the discrimination against women worsens. The female employees discover that they are given the most difficult clients, not because they are adept at handling delicate situations, but to spare their male co-workers from getting “tired out.” Of course, women are paid less. “The gender pay gap in Korea is the highest among OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries. According to 2014 data, women working in Korea earn only 63 percent of what men earn…Korea was also ranked as the worst country in which to be a working woman.”

The crowning horror is when a hidden camera is discovered in the women's restroom. A male employee has been filming and selling images of the indisposed women. Some of the viewers are men at the company who recognize the women and instead of reporting the abuse, they share the photos! The male director of the company will not officially apologize to the victims, nor promise to take preventative measures, nor punish the participating men because, “It'll ruin this company's reputation…The accused male employees have families and parents to protect, too. Do you really want to destroy people's lives like this?”

A bit of research revealed that this practice of secretly filming women in public bathrooms and changing rooms is a chronic problem in South Korea. The crime is known as molka or “illegal filming.” Images are posted on social media sites like Twitter and Tumblr and the full video may then be purchased. According to South Korean police files, reported molka crimes increased from 1,353 in 2011 to 6,470 in 2017. A study by the Korean Women Lawyers Association found that only 31.5 percent of those accused of committing molka crimes in 2016 were prosecuted. Between 2012 and 2017, only 8.7 percent of those tried for the crime received a jail sentence.

This is the reality Cho Nam-Joo wanted to expose in her novel. The gradual grinding down of the psyche—in school, work, and family—as reinforced by the culture is often as detrimental as one traumatic event. Cho asks, “Do laws and institutions change values, or do values drive laws and institutions?” The book caused a sensation in Korea, where it sold over a million copies, and launched a protest movement for women's rights. Jiyoung's ordinariness connects her to every woman in Korea and beyond.

The unresolved ending disappointed me, yet that is Cho's point. There is no way to resolve Jiyoung's issues, because the issues of sexism in Korea are unresolved. Perhaps the dry clinical narrative voice is necessary to make readers accept the facts. This voice, we realize, belongs to Jiyoung's male psychiatrist, who is notating events in her medical record. The book is important, but the somewhat pedantic, dull tone almost caused me to stop reading. Consider this book as if it were nonfiction, for your education and the illumination of a systemic problem rather than as a novel, and it becomes worthwhile.

Purchase the book here.

Diane Englert is a writer, actor, accessibility consultant and provider. She writes for the website Write or Die Tribe and her work also appears in Ruminate Magazine, From the Depths, What Rough Beast, and We’ll Never Have Paris. She wrote libretto for several mini musicals that were all produced. Diane has a BFA in theater from University of Utah and an MBA from Marylhurst University.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982

by Cho Nam-Joo

Examines Misogyny

Book Review

by Diane Englert